After the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the mental health crisis in the United Kingdom worsened. The number of people in contact with NHS mental health services increased from 3.6 million to 4.5 million between 2016-17 and 2021-22, which shows how many people need care and support for their mental health.

Some people who experience a mental health crisis are admitted to the hospital, to receive inpatient care and wrap around support, helping to keep them safe. Some people will be detained under the mental health act, and enter hospital under a section, meaning that they can’t voluntarily leave.

When patients are ready to leave hospital, the doctor will have assessed their needs and decided that they are safe, but some people still require some help and support in the community.

I like to explain it as being the same as physical health needs. When someone breaks a bone, or suffers an injury, they might undergo surgery but still require rehabilitation and support once they return home. It is the same for mental health needs.

‘I relapsed after my first admission, because I had no help’

22-year-old Liv, lives in Scunthorpe, South Yorkshire. At 17, she was admitted to an adolescent psychiatric hospital, under the mental health act.

Liv spent her days living in a clinical ward, surrounded by other poorly teenagers. Inside an adolescent ward, you will often find some areas that feel ‘normal’ including: games rooms, sensory corners, televisions and schools. However, behind the visible features there are constant alarms, physical restraints between staff and patient, and people who harm themselves regularly both behind doors and in the company of others.

At 18, Liv was transferred to an adult ward – fewer activity corners, absolutely no education and fewer peers her own age. Liv had to move to another ward as she was still detained under a section 3, but couldn’t stay on an adolescent ward, as an adult.

After spending some time in the adult facility, Liv was eventually discharged to her family home, to continue her recovery surrounded by those she loved. However, the continuing care from community mental health teams was poor.

In a chat with Liv, she told me that, “The support was practically non-existent. I wasn’t offered any therapy or enhanced support and I only sporadically saw my care coordinator, which didn’t benefit me, as it was always very superficial conversations.”

For someone who spent the best part of a year in a clinical mental health setting, the need for ongoing support was still required. Liv no longer had 10-minute check-ins from staff members, no anti-strangulation furniture, no clinical medication rooms, making sure drugs are controlled under lock and key and most significantly a limited number of people to talk to. She had been ‘thrown in the deep end.’

Once in the community, clinical support is not expected, or even realistic, but section 117 is there to help provide support with: medication and the administration of medication, continued psychiatric intervention and therapy, supported housing and access to day centres. As a whole, aftercare supports the next stages of recovery, without leaving patients with nothing to prop up against.

Liv relapsed after being discharged at 18, telling me that in the times that she was really struggling, she was ‘shrugged off’. In 2022 she was readmitted to hospital, after relapsing with an eating disorder.

“My mum noticed that my weight was significantly declining and contacted my care coordinator to explain her concerns, but it wasn’t treated as any kind of priority, and it took my care coordinator at least 5 weeks to arrange a visit to come see me.”

Liv’s second admission could have been prevented if she had received the appropriate and needed support when she was at home. Liv continued to explain that she was discharged in August 2023, at the age of 20, again with zero support, but this time based on false promises.

“I was told prior to my discharge that I would receive therapy from my community team under section 117 aftercare.”

I had asked Liv whether she had any documents or evidence showing that section 117 was part of her discharge plan, but she said it was all verbal and never formally noted.

The need for Liv to continue with therapy and psychological intervention was essential in continuing her recovery. However, Liv was told by her local mental health team that she couldn’t access therapy whilst living at her parents’ address.

“My care coordinator has still been stalling the process by coming up with excuses, such as her team haven’t had time to speak about me. I was told in January 2024 that they won’t be able to offer therapy whilst I’m still living at my home address, and I think it is an invalid reason. The staff at the eating disorder hospital I was in agreed with me.”

Liv now believes that the aftercare she received contributed to her relapse, as she was discharged from an intense unit with constant monitoring, to nothing.

The community team, which Liv was transferred to, is part of the North Lincolnshire Clinical Commissioning Team. I have approached them for a comment on Liv’s case and submitted a ‘Freedom of Information’ request to dig deeper into why mental health support is being neglected.

Humber and North Yorkshire Integrated Care Board Response

Humber and North Yorkshire ICB, now encompassed with North Lincolnshire CCG, provided me with the details of the amount of funding that goes into supported living, care home nursing, residential placements and 1:1 support.

| 2020/21 | £952,757 |

| 2021/22 | £1,184,139 |

| 2022/23 | £1,308,659 |

| 1/4/2023 to 29/2/2024 | £1,165,062 |

This shows that there is money being spent in the care sector, but where is it spent exactly?

After receiving the information from Humber and North Yorkshire ICB, I looked into the joint-funded care through Scunthorpe Council, which deals with specific care plan arrangements; I am still awaiting the details of this funding.

However, Scunthorpe isn’t the only local authority failing to provide aftercare that patients are entitled to.

From supporting others to being supported

Sarah is 33-years-old and was working in the same ward that Liv was being treated in at 17. Sarah also struggles with her mental health and is currently detained under the mental health act, in hospital.

Doncaster resident, Sarah is a mental health professional, but sadly now a patient. Over the last three years Sarah has spent time in and out of hospitals, miles away from home.

During her first admission, Sarah was sent to a hospital in Birmingham, as there were no beds available close to her home, which is something commonly found in mental health admissions. This was an ‘isolating’ experience, according to Sarah.

There have been many occasions where Sarah has desperately wanted to go home to be closer to family, friends and the environment that she knew. However, the hospital wouldn’t accommodate this, because of expenses; Sarah knows as a former healthcare professional that going home, for some patients, is a therapeutic activity and can really aid someone’s recovery, beyond the four walls of a psychiatric unit.

Sarah is currently in hospital as an informal patient, after being readmitted to a section not long after she was discharged from Birmingham. Still, she struggles with the transition back to her ‘normal’ life, as her community team won’t support her having day trips and smaller visits home, preparing her for discharge. Instead, she is left with no income, trapped miles away from her loved ones, unsure as to what her next steps are.

The lack of intervention from Doncaster authorities, or the RDASH mental health group, is something that has crossed my path before.

A distinct failure of care

In September 2022 Anthony was discharged, from a high security mental health hospital.

My brother spent three years in high security environments, due to complex mental health needs.

At aged 21, he moved into a residential care home, where there would be wrap-around care and support for him, whilst also allowing him independence and new opportunities. With so much promise, with anxious excitement, our family felt hopeful for Anthony’s new future.

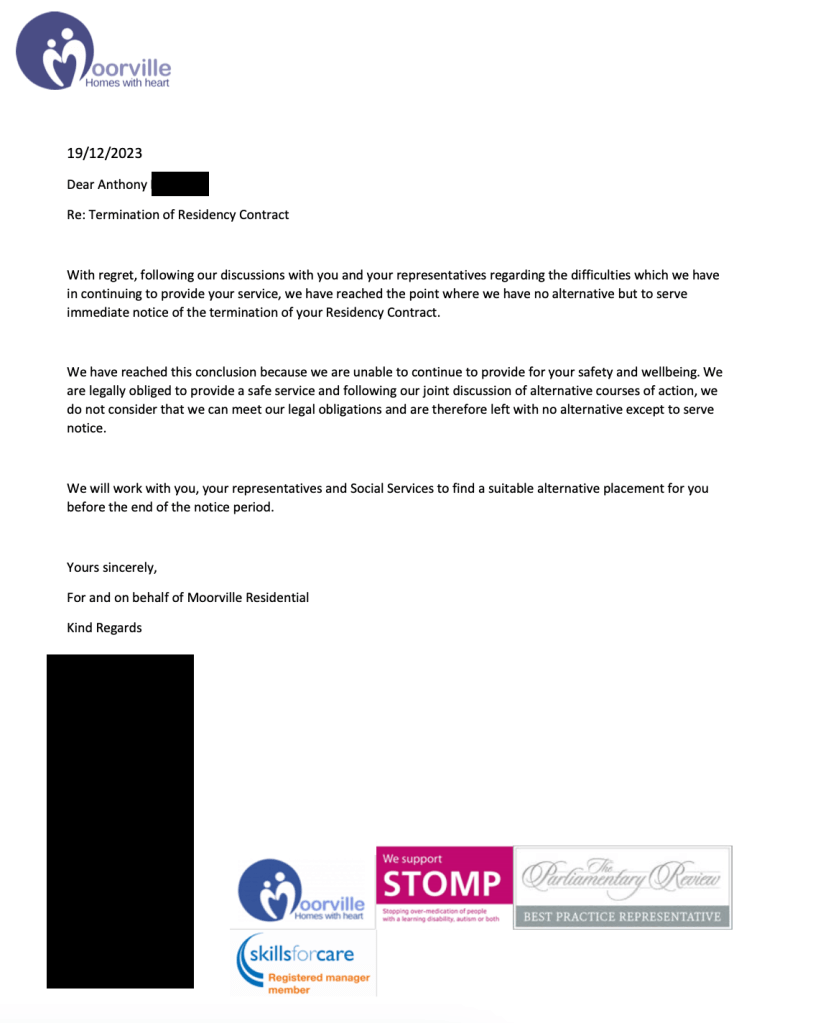

However, after Doncaster provided the funding for Anthony’s aftercare, he moved into Moorville, a supported home in Sheffield. He settled without major problems and was simply itching to reunite with the outside world. He felt excited to have independence and ‘normal’ life back.

Despite this, as someone who has complex mental health needs, Anthony did face some teething problems, which the staff at Moorville found difficult to manage.

On the official website, Moorville Residential claim to have a team who, “are fully trained in line with all current legislation and our regulatory body, the Care Quality Commission (CQC).”

Moorville also claims to “provide its [our] staff with bespoke Autism Awareness Training created by Angela Austin – a renowned expert in this field.”

With professional training in place and a stated understanding of the needs of the vulnerable people within their care, they still failed Anthony the day they made him homeless.

“Moorville was established in 2008 with the intention of creating a high-quality, personalised residential service for those with autism and other support needs. We are a family run business able to bring a personal touch to the care that we provide.”

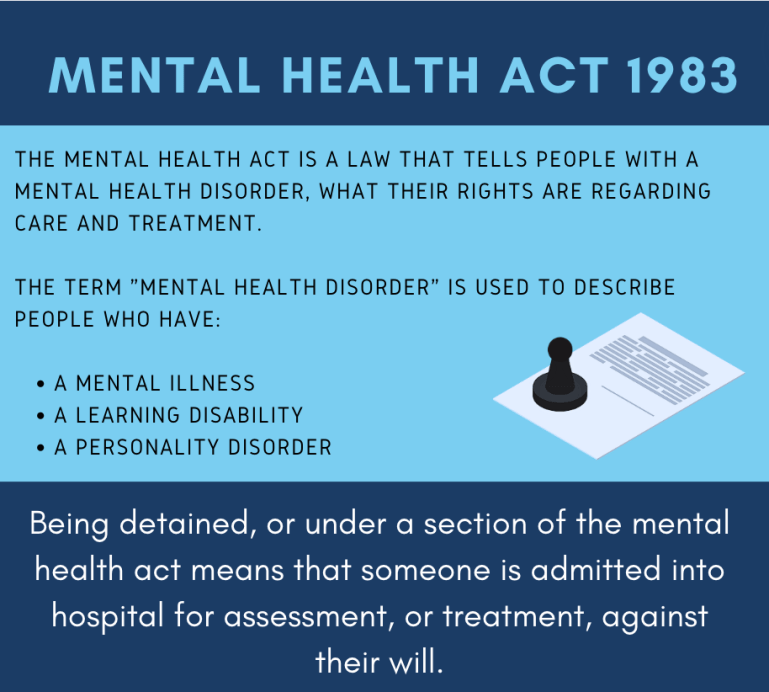

On December 24, Christmas Eve, my mum was informed that Anthony had received a ‘no notice eviction’. They gave him only hours to figure out his ‘next steps’ – a boy with severe mental health and additional needs.

Anthony had nowhere to go.

A lot of Anthony’s care team and social workers had taken annual leave over the Christmas period, and the harsh actions of Moorville ruined Christmas.

I contacted Moorville Residential, to ask for a response on the decision to make a vulnerable person homeless, at a time that he needed support. I didn’t receive any response.

Thankfully, some of Anthony’s team were on board and recognised the brutal extent of the situation and he was placed in a hotel, in the centre of Doncaster.

The hotel is being used to home asylum seekers and the homeless – no cooking facilities, no laundry facilities and no comfort. Luckily, Anthony has a supportive family and his mum wrote a letter on his behalf, addressing the deepening concerns of his care.

Anthony was suffering from a chest infection and in March 2024, just before he left the hotel, discovered that his pillow was covered in mould. The environment was unclean, cold and not somewhere that Anthony could begin to engage in psychological therapies and further his recovery in the community.

I contacted RDASH, who is involved in the community care and treatment of patients in Doncaster, to find out what support they offer around section 117, and how much funding is being invested.

They offered this response:

“The Trust takes all of its legal obligations very seriously, having a dedicated committee of the Board to oversee its delivery. Section 117 is an important element of this. Of course, we keep under constant review the way in which we best safely, and compassionately, do this, recognising the strain on services and communities from wider funding pressures.”

South Yorkshire Integrated Care Board (ICB) also responded with this detail:

“Doncaster Place, in conjunction with City of Doncaster Council, commission Section 117 aftercare in line with identified care needs of individuals. This is based on a Section 117 statement of need which is completed by the individuals MDT, a care package is identified to meet identified need and presented to a weekly multi agency panel for agreement. Care provided can be in the form of care in their own home, in a supported living or care home environment. Doncaster’s spend on Section 117 aftercare in 2022/23 was £14,112k.“

Arguably, Anthony has received some level of care, as his housing and support is being funded by Doncaster social care. However, the levels of care are poor, as exampled.

From the time that Anthony was evicted from the residential home, to the hotel for homeless, he has been supported by our mum and care team.

He had a brief period of allocated 1-1 support, at certain times in the day, but still this failed.

On one evening, Anthony was in the town centre of Doncaster and his support worker supposedly left Anthony to grab a bite to eat. In the time he left Anthony’s vicinity, a group of men attacked Anthony, taking his phone, money and leaving him quite shaken. Luckily, with police intervention, his possessions were found and returned, but the impact on Anthony, as a vulnerable young man, was heavy. Anthony explained that he has complained about the care he received that evening, and when I spoke to him about the night, he said that the staff member had now left.

Anthony has now successfully been transferred to a new residential home, where support and care is in place. Now he can spend his days focusing on his mental health, without fear or anxiety.

Supporting evidence from the NHS Ombudsman

In 2012, The NHS Ombudsman service published a report on section 117 aftercare, regarding the case study of Mrs and Miss M. Titled, ‘A report by the Health Service Ombudsman and the Local Government Ombudsman about the provision of section 117 aftercare’, the document outlines a complaint of care, similar to the stories of Liv, Sarah and Anthony. The report showed: “The failure by the Trust to consider Mrs M’s eligibility for section 117 funding at any contemporaneous stage was maladministrative. We now consider whether this maladministration by the Trust was the cause of an injustice to Mrs M.”

The case study of Mrs M dates back to the 90’s, when she first suffered with her mental health, under the Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust and Wiltshire Council; It was her daughter who made the complaint regarding her mother’s care.

Within the report, it states: “The Trust and the Council failed to properly assess and provide for the health and social needs of her mother… from 2004 until her death in October 2009. In particular: The Trust’s explanation that her mother was not covered by section 117 of the Mental Health Act 1983 was ‘unreasonable’, in that her mother was entitled to receive aftercare services under the provisions of section 117.”

“The ombudsman investigated complaints by Miss M that it was wrong that Mrs M had been expected to fund her own care in the Care Home – that this should have been provided under section 117 of the Mental Health Act 1983. Miss M complained that the explanation she had been given about her mother’s ineligibility for section 117 funding, by the Trust, was unreasonable.

The report shows that the Trust didn’t provide ‘consistent’ explanations about Mrs M’s discharge from section 117 aftercare, and the rhetoric kept changing. The report also states that, “They [the Trust] could not provide any evidence of a multidisciplinary meeting to confirm that Mrs M had no longer been eligible for free aftercare services.”

To support the complaint, there is professional input, from medical and nursing professionals, who supported that, “there was no evidence that Trust or the Council appropriately decided that Mrs M no longer needed aftercare services under the provisions of section 117 in 1989, 1996, or at all.”

It was also advised that there should be a ‘clear paper trail’ for patients entitled to receive aftercare services in line with section 117 and that it should be included in ‘documentary evidence’. However,there was “no evidence of any such meeting’.

Despite the evidence showing that Mrs M had been neglected of aftercare services, and more significantly, the lack of documentation from the council and the trust, the overall report concluded:

“we cannot say with any degree of certainty that the admission to the Care Home can be linked directly to aftercare needs that might have been present in 1989. We cannot, therefore, conclude that the failure to consider Mrs M’s eligibility for section 117 definitely led to an injustice to her or her family.”

“The evidence we have seen does not support a conclusion that the Trust and the Council failed to assess and provide for her mother’s health and social needs properly from 2004 until her death in October 2009. Therefore, we do not uphold Miss M’s complaints.”

The full report can be found here: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7cbd3de5274a38e575674e/0642.pdf

“The mental health act is outdated”

The improvement of community mental health services and local mental health trusts is something which, supported by this investigation, should be recognised by councils and trusts as a crisis in mental health aftercare.

In 2023, the government set out a proposed investment of: “£2.3 billion of additional funding a year by March 2024 to expand and transform mental NHS health services, so an extra two million people can get mental health support.”

The same article outlined that the ‘funding for mental health is expected to increase to 8.92% of NHS funding in this financial year.’

Through just three stories from people who have experienced a lack of aftercare, after receiving hospital treatment for their mental health, it is evident that these services are being neglected and need addressing.

When considering previous Ombudsman complaints, of a similar character, more than a decade down the line the same missing ‘papertrail’ of reports are still missing.

Despite being given the statistics on the amount of money being invested in community mental health care, specifically section 117, it could be argued that the issue is not the funding, but where the funding is going and whether there is a papertrail to follow that too.

People like Liv, Sarah and Anthony have all faced the harsh reality of going backwards, after reaching stability. Had they had been treated with more thought and care, their stories might have been different.